The three realms of Arianrhod

I know all the names of the stars from North to South;

I have been in the galaxy at the throne of the Distributor…

I have been three periods in the Prison of Arianrhod—Hanes Taliesin

Ancient poets spoke of a revolving castle where brave travelers could claim the gift of inspiration. Within this spiral tower, the powerful star goddess Arianrhod ruled over the cycles of death and rebirth. Those who touched her realm and lived to tell of it became prophets, endowed with clear sight and silver tongues.

But how did they get there?

The way wasn’t easy. It required a deep understanding of the Celtic cosmos, which encompasses three realms: land, sea, and sky. The land comprises the physical world we live in. The sky consists of the upper realm, or heavens. The sea serves as a boundary between our world and the lower realm, or underworld.

Like the ancient Greeks, the Celts placed their gods in the heavens by mapping their mythology to constellations in the night sky. But their gods didn’t just exist in the upper realm. They also resided here on Earth. Britain is full of physical sites, on both land and sea, where the gods were said to have dwelt.

Arianrhod’s castle is one such place. In myth, Caer Arianrhod was the place where human souls were said to travel upon their death. It existed in all three realms at once, each separate and distinct, and each serving as a portal to the others. Those who knew the way could use the Caer’s revolving door as a gateway for traveling between worlds.

Land—Sunken island

Under the water Her icy castle sleeps. The legendary ruins of Caer Arianrhod are quietly hiding under the waves.

Stand on the northwest shore of Wales at low tide, and you might catch a glimpse of the sunken reef believed to be the site of Arianrhod’s earthly home.

In Y Mabinogi, her son Llew travels by ship to reach his mother’s fortress. The poet Taliesin wrote of a “caer of defense under the ocean’s wave.” Local legend places Caer Arianrhod about a mile off the coast of Gwynedd, which is also home of Glastonbury Tor—the legendary site of another mystical island, Avalon.

According to a 1904 geological survey, the submerged castle of Arianrhod lies in a “stony place” in Caernarfon Bay not far from the prehistoric mound of Dinas Dinelle. It’s an oval reef measuring about a quarter of a mile from east to west and a tenth of a mile from north to south, with a submerged area of stony ground connecting it to the mainland. Its west end rises to a low summit, which is briefly visible during the lowest spring tides, when white horses were said to “dart and play” upon the surf.

It was said that she lived a wanton life, mating with mermen on the beach near her castle and casting her magic inside its walls.

—The New Book of Goddesses & Heroines

Some say artists and magicians visited the island to gain advanced training, inviting a comparison to the sophisticated civilization of that other sunken city, Atlantis. At one time, the island would have been on dry land and forested, according to ancient sea level studies, and archaeological evidence suggest human inhabitants from as early as the Neolithic period. But was there really a city there?

“No convincing traces of artificial features can be seen in the shallow water around the reef, although there are suggestions of some regular wall lines and a ‘D’ shaped structure closer to the shoreline, possibility associated with coastal fishing industries,” says the National Monuments Record of Wales.

Richard Marsh has taken some haunting photos of the site. And check out this image of the sun setting over its submerged remains.

Sky—Northern Crown

There is a cross amid the evening sky,

When summer comes again;

There is a crown which sparkles clear and high

Above the homes of men.—The Cross and the Crown

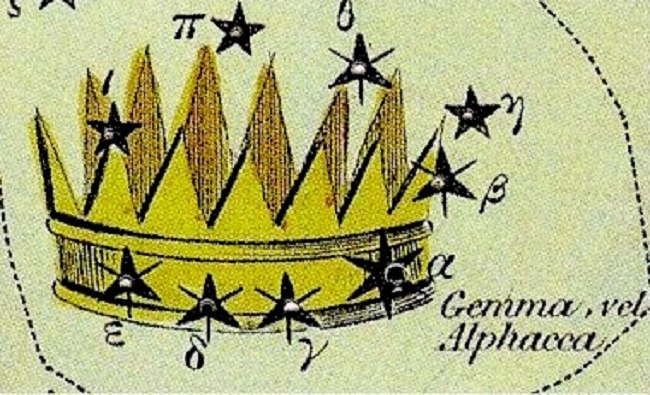

Gaze up at the night sky and look for seven stars arranged in a semicircle. This is the celestial realm of Arianrhod, whose name means “Silver Wheel” and who was said to inhabit a spinning fortress among the stars.

Caer Arianrhod is the Welsh name for the constellation Corona Borealis, which means “Northern Crown.”

As the starscape revolves in the sky, the Corona Borealis traces its path around the central North Star, dipping below the horizon and rising again. In the silver wheel of the zodiac, it stands opposite the Pleiades, a circle of stars traditionally associated with weaving goddesses; the two trade places in the sky every 12 hours. Celestially speaking, Caer Arianrhod crosses the axis of the North Star to take the place of the Pleiades, just as in myth Arianrhod steps over Math’s wand and gives birth to twins, says Welsh scholar Mike Harris.

The Corona Borealis is also said to be the crown of the Greek goddess Ariadne, who spun out a thread to guide Theseus out of her labyrinth—another fiber connecting Arianrhod’s starry domain to the arts of spinning and weaving. Some say she spins out the fate of the world from her starry domain, which is often described as labyrinthine.

Ariandrhod’s celestial castle bears the shape of both the crown, a symbol of sovereignty and enlightenment, and the cauldron, a vessel of at transformation and inspiration. The cauldron is most heavily associated goddess Ceridwen, Arianrhod’s crone counterpart. Ceridwen’s caer was the rainbow, and Arianrhod was said to cast a rainbow of protection to shield her people against strife.

Arianrhod, of laudable aspect, dawn of serenity

The greatest disgrace evidently on the side of the Brython,

Hastily sends about his court the stream of a rainbow,

A stream that scares away violence from the earth.—The Chair of Ceridwen

Arianrhod’s stellar Caer is also related to the Milky Way, which is known as the fortress of her brother, Gwydion. There’s an eerie similarity between Arianrhod’s constellation and her sunken reef, according to blogger John Toffee. A visual comparison between the Corona Borealis’s relationship to the Milky Way and the island Caer’s relationship to the Welsh coast reveals an “uncanny topographical resemblance,” he says.

“One is reminded of the ancient dictum, ‘As above, so below.’ ”

Sea—Otherworld fortress

My beloved is below,

In the fetter of Arianrhod.—Hanes Taliesin

The final fortress of Arianrhod can’t be found either on land or in the sky. It can only be entered by piercing the veil between this world and the Otherworld—a realm of spirit that exists in tandem with our own.

The Druids believed at certain times of year the veil between worlds grew thin, opening a portal to the Otherworld. Caer Arianrhod represented “the ‘revolving door’ that allowed access to the world of the Sidhe, or fairy people,” says Phyllis Vega, author of Celtic Astrology.

In Celtic myth, crossing the boundary into the spirit world often involves passage over water, just as in Greek mythology the souls of the dead must traverse the river Styx to reach the underworld. It’s only fitting, then, that Arianrhod’s Otherworldly Caer belongs to the realm of the sea.

Both the land and sky Caers “are, in a sense, signposts to the Otherworld Caer Arianrhod, for neither a fortress in the night sky nor one at the edge of or under the sea are completely of this world,” say Carl McColman and Kathryn Hinds in Magic of the Celtic Gods and Goddesses: A Guide to Their Spiritual Power.

The Otherworld Caer, they add, “is a place of changes and transformations.” Arianrhod is both enchantress and initiator, a stern taskmistress who lays heavy limits upon her initiates. None who enter her fortress emerge unscathed. When her Lleu visits his mother’s earthy fortress, he also crosses into the Otherworld. Physically, he receives a name and arms. Spiritually, he transforms from a boy to a youth to a man.

In some traditions, it is Arianrhod who ferries the dead on her Oar Wheel to the land of death to await rebirth. As the ruler of reincarnation and karma, she oversees their souls until they’re ready to be spun back out on her wheel of creation. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore describes this Otherworld as “beautiful and unchanging, not entirely unlike our world but without any pain, death, disfigurement, or disease.”

It is a world that may be touched and even visited—during death or dreams or visions or initiation—and there are some, like Taliesin, who can remember and tell about it afterward.

—Celtic Gods and Goddesses

Many folk within the Celtic tales, including Arthur, wind up trapped in Arianrhod’s spiral tower. Those who enter her labyrinth find it exceedingly difficult to leave of their own volition—and those who do return bring with them the gift of prophesy. Taliesin claims to have visited three times to gain the arts of clairvoyance and poetry. The Scottish prophet Thomas the Rhymer spent seven years there, emerging with clear sight and a silver tongue.

Success is not assured. For those who choose to travel between the three realms of Arianrhod, the journey requires both courage and fortitude. Few have dared to make the journey, and even fewer have returned to tell of it.

If you linger here, transfixed by the beauty of what you see, then you will be a captive forever.

But, if you have the strength to turn and walk out of the Spiral Castle,

then the hidden secret of House Arianrhod will be revealed to you.

After that, all that remains is to take possession of what is yours.—Becoming the Enchanter

Featured image by Eric Jones—Caernarfon Bay from Ro Bach Beach, CC-BY-SA-2.0