The goddess has no face

Who is the Goddess of the Beginnings, then, who has genitals but no face?

—Jean Markale, The Great Goddess

One night several years ago, I journeyed down a moonlit inner path to meet the Lady. I found her in a copse of trees, on the edge of a deep forest. She stepped into a clearing and let the silver light fall on her face. She was beautiful.

Then she changed.

Every time I blinked, she wore a different face. Her hair shifted from black to gold to red. Her eyes became dark pools of mystery, then blue as sky. The more I tried to hold a single image of her, the faster her faces slipped away.

In my first encounter with the goddess of the Wica, I learned that she has no face.

You could, of course, just as truthfully say she has many faces. Maid, mother, crone. Star goddess, moon goddess, earth goddess. So many names. So many aspects. You could just as truthfully say she has no face of her own because she wears the face of All.

Listen to the words of the Great Mother, who was of old also called Artemis; Astarte; Diana; Melusine; Aphrodite; Cerridwen; Dana; Arianrhod; Isis; Bride; and by many other names.

—Doreen Valiente, “The Charge of the Goddess”

But I love her best when she has no face.

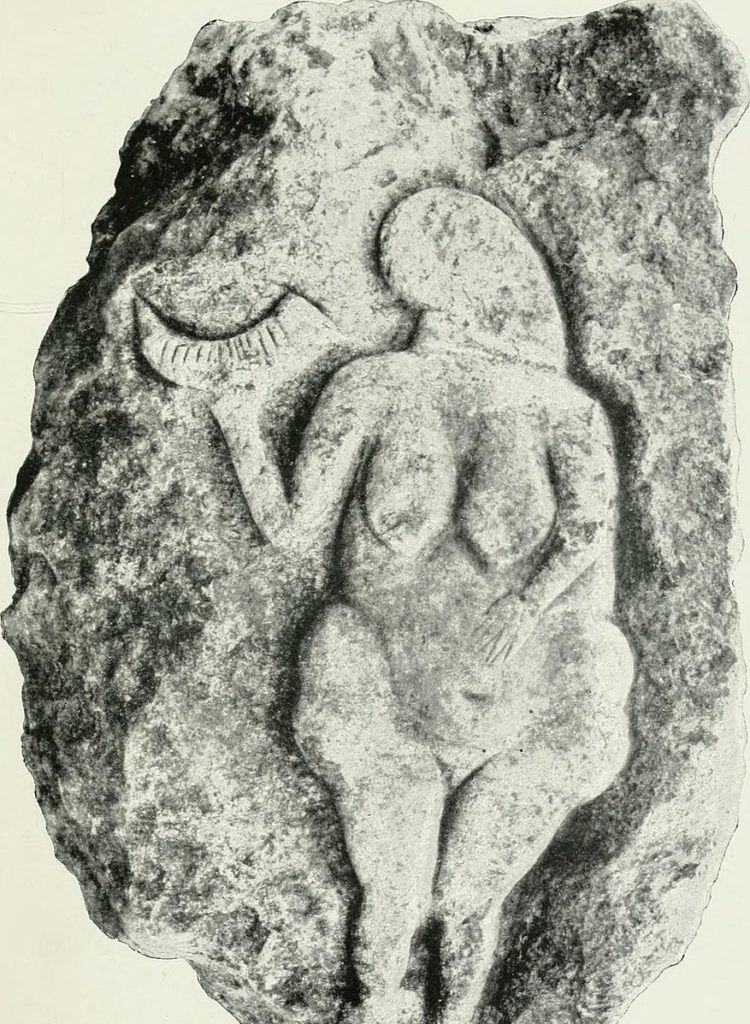

If you look at paleolithic cave paintings and figurines such as the Venus of Willendorf (above), they often depict a great mother goddess with no face. Anthropologists can make all sorts of guesses as to why. Maybe they depersonalized their images to make it clear they represent transpersonal forces rather than individual people. Maybe those early artists simply couldn’t imagine features beautiful enough to belong to her.

To be honest, I don’t often see a goddess statue I like. It’s the faces that bother me. Even when the symbolism is all there, something about the face just isn’t quite right to me. When I mentioned this to a witchy friend, he said the facial features shouldn’t matter. It’s the energy of the piece that counts.

But that was exactly my point. The more rudimentary the image, it seems to me, the more it captures her essence—and the more her energy comes through. More often than not, the face just seems to get in the way.

Having tried to paint her myself, I suspect we just weren’t meant to pin a face to the goddess. Even in myth, she’s always changing. One minute she appears as a hideous hag, the next she’s a beautiful princess. Or an animal. Like Joseph Campbell’s mythic hero, she wears a thousand faces, and she can change them without warning. Beatific mother one moment, merciless devourer the next.

Of course, some goddesses do seem to wear their faces proudly. Medusa wouldn’t be the same without her snarl of rage, nor Kali without her unfurled tongue dripping blood. But these vivid expressions can also be flattening, conveying only one side of a complex, multi-dimensional archetype. Medusa is a sensuous beauty as well as a blood-freezing monster. Kali gives life with one hand even as she takes it with the other.

We have a tendency to want to humanize—even sanitize—the goddess for ourselves. I think we have trouble grasping her complexity, her paradoxes, her totality. She’s much easier to deal with in bite-sized aspects. Maybe it stems from fear. We devour her before she can devour us.

But knowing the goddess means becoming comfortable with the unknown. It means letting her be faceless.

Maybe Isis has the right of it. She wears a veil no mortal can penetrate. The Veil of Isis represents the mysteries of the universe not meant for our comprehension, and she protects us from them as much as she guards them against our seeking. The hidden face of the goddess remains hidden for a reason.

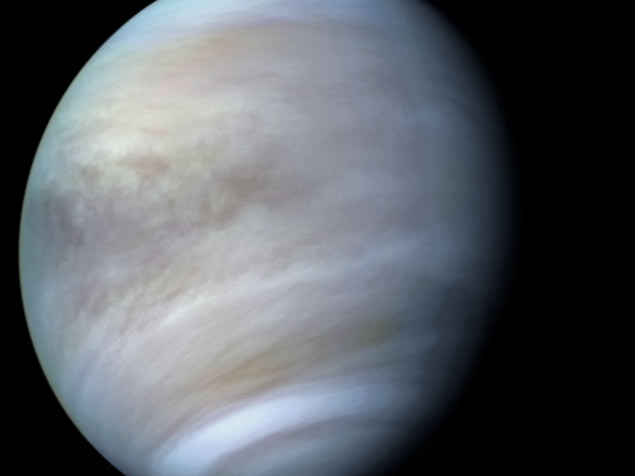

That doesn’t stop humanity from trying. Take Venus in her star form, for example. In 1761, Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov noticed that the planet had a dense and opaque atmosphere that veiled her surface from view. For 200 years, people fantasized about what lay hidden beneath her clouds. It took seven attempts before they made it past the crush of her atmosphere. What did they find?

Carlos Julio Pino Villarroel writes:

There were no jungles, no swamps, no dinosaurs, hidden behind the shine of the morning star. Instead, this was a boiler at almost 500 degrees Celsius, asphyxiated by carbon dioxide, receiving the constant sulfuric acid rain being released by its volcanoes. Such was the true nature of the hidden face of the goddess, very different from what we expected, but no less beautiful.

Such is her true nature: Sometimes terrible. Always beautiful. Never what we expect.

The goddess hides her face for a reason.

Featured image by Captmondo—Venus of Willendorf, CC-BY-SA-3.0